It goes without saying that this has indeed been a difficult few years. Last year as we welcomed in the new year we were negotiating our feelings and response to October 7 and its aftermath. This year, we find ourselves in a place perhaps we didn’t expect, as hostages still languish in captivity and this intentional human-created tragedy in Gaza has gotten so much worse. Last year we were on the cusp of a Presidential election. This year we find ourselves in a country we perhaps don’t even recognize, marching steadily toward authoritarianism, eroding democracy, increasing physical, verbal, and legislative violence.

Happy New Year.

As I was thinking about what I wanted to share approaching these days, I took solace in the saying, usually attributed to the mussar master Rabbi Israel Salanter, “A rabbi whose community does not disagree with them is not really a rabbi.” I know too that I have two opportunities to share with you over these days, tonight and Erev Yom Kippur. So we will see how it goes. How to be a support to you, how to be a guide to you, while negotiating my own feelings has been the path I have had to navigate this past year.

And as you know, I have always looked back to the past year to offer reflections for this year. And while the world has felt strange and foreign, we all have marked our personal milestones. For one, I became the parent to two adult children, and that has been an interesting and exciting transition that Yohanna and I are navigating.

And perhaps at some point there will be an opportunity to reflect on that. But other matters seem more pressing. Since the election, I have written some and posted on social media less thoughts about what this moment means, but what this moment demands. How are we to respond? And by we, I mean those of us who are committed to values of justice and equity, community and compassion. In other words, as I would posit it, those who are committed to Torah. Because these are the values that Torah embodies.

So I went back to these teachings, and I bring them forward. And as we stand at the cusp of this new year, in my tradition of offering you lists on Erev Rosh Hashanah, I offer you 7 Ways that We can Meet this Moment.

1. Make Your World Small

Things are so overwhelming right now, and its very easy to feel powerless. Part of our power however comes from shifting our perspective. In the face of this overwhelm, we can make our world small, and without losing sight of the bigger picture, focus energy on who around us needs help right now. For there are people in our immediate circles who are at risk, whose foundation is crumbling, who are living in real fear.

Who are the immigrants in our community who are in fear of ICE, wary of going to school or work or just outside for fear that they will be targeted and caught up in these sweeps. Show yourself to be an ally, take a know your rights training, be a monitor and disrupter of crackdowns that would seek to deny people’s rights and their freedoms.

Who are the trans folks in our community whose lives and identities are threatened? Recognize the real fear. Remind people that they are welcome here, and be welcoming. Use correct names and pronouns and don’t get upset if you are corrected. Learn and grow and welcome.

Who are the folks who are isolated, withdrawn, who need attention and love? Particularly we have seen young adults, young men radicalized online through the absence of social structures and connections. If they don’t get it they will seek it other places, and we have seen that to have terrible consequences.

Who are those whose access to health care, or food, or basic services is being undercut, and how can we provide aid for them?

And it is not just about protecting the vulnerable, we need this strong communal attachment not only to resist, but to subsist and persist. We need to share our fears and hopes. To have authentic human interaction. This type of community building and relationship building is critical: critical for our own well-being, for the well-being of others, and the well-being of our society.

How can we look around, and do what we can in our own community, our own sphere of influence, and make our world small?

2. Hold the Door

This rule is not in the Torah, but maybe it should be: when you are going through a door, always look behind you and see if there is someone there, and if there is, hold the door for them.

This is an act of common courtesy. And I’m sure if you have been at the receiving end of a door closing on you, you experienced as rude and dismissive. Or even more, that you felt unseen, unacknowledged, unworthy.

When we fail to hold the door, we are committing what I would posit is one of the biggest sins we can commit, because it leads to other sins. It is the sin of dehumanization. It is the failure to see that we are all created, as Torah teaches, betzelem Elohim, in the image of God. We see how dehumanization allows us to cause real injury—on the personal scale, on the national scale, on the global scale.

We need to fight the forces of dehumanization. And it begins with us in our day to day. By holding the door. By learning peoples names and using them. By, as we learn in Pirke Avot 1:15:

וֶהֱוֵי מְקַבֵּל אֶת כָּל הָאָדָם בְּסֵבֶר פָּנִים יָפוֹת

“Greet everyone with a pleasant face.” See each other as a whole self. When we see each other as fully human, we can not harm them.

It think about this when I think about our Greeter Corps here at TBH. I’m sure you met some of our wonderful greeters when you came here this evening. It’s our practice to have greeters stand by the door, to be a welcome presence, to hold the door open for others—not just physically, but emotionally and spiritually. And it is a reminder that it is so easy to be unwelcoming—with overt actions, with unintended words, with well-meaning microaggressions. These are things we need to be mindful of, learn about, and grow past.

And holding the door reminds us of thinking of not only other people, but those who come up behind us. Those of us with privilege and access need to think who is coming up behind us, who may not share in that privilege and access, and we need to be sure we are inclusive to everyone.

3. Care about Solutions not Slogans

There is much to be said about our political discourse these days, but not just political discourse, any discourse—that what gets attention is short, easily digested videos and slogans, meme culture. I admit, I am guilty of this, as I have used social media a lot as a platform for teaching Judaism.

I see how the messages get distilled and simplified, and that the problem is that these slogans can be prone to misunderstanding, and a reductionism that undercuts any meaningful progress. For we overlook the fact that underneath these slogans, we’re talking about real people.

So we need to move beyond slogans and focus on solutions—how can we get to where we want to be. We see that our government is advocating a series of policies all in the name of “small government” or “waste, fraud, and abuse” or “freedom.” But these policies are privileging the few over the many, increasing inequality and causing real harm. And we know too that as we look broadly, any solution in Israel and Gaza is going to need to take into consideration the future of both Palestinians and Israelis. Single-minded solutions will only perpetrate systems of oppression and domination.

Slogans are fine, they can be effective in advancing a cause. But again as we learn from Pirke Avot 1:15:

אֱמֹר מְעַט וַעֲשֵׂה הַרְבֵּה

“say little and do much.” Words have consequence, words can be violent. And we are judged by our actions, not words (at least, we should be), and we need to remember that whatever we are advocating, we are doing it for people, all people—uplifting their hopes, dreams and safety—humanizing and not reducing them.

4. Play the Long Game

The Exodus from Egypt was supposed to be a short trip. After crossing the Red Sea, our spiritual ancestors travelled a few days to Mount Sinai where they spent a year in preparation, including accepting the Torah from Moses. They learned the rules and practices. They built institutions like the Tabernacle and the priesthood. They established communal norms and roles. And after that, it was only a few days journey into the land.

But we know that is not how things went, the Israelites spent 40 years wandering in the desert. And it wasn’t a mistake. On one level, the 40 years was a punishment for an apparent lack of faith of the Israelites in God’s plans. That’s how the text reads when we read the story in the Torah. On a deeper level, however, we can understand that the 40 years is a necessary step to societal change. God recognized that the generation that left Egypt was too burdened, too traumatized, and could not be the ones to fulfill the vision of a new society. It would need to be the next generation that took those important next steps.

I think we Jews have become the masters of the long game. Despite two thousand years of efforts to eradicate the Jewish people, we are still here. And so this is perhaps something we can carry with us as we face this current reality.

We are seeing, however, how fast it can be to tear down what took so long to build. But what might feel unprecedented to us, is not in the scope of history. Social change that seems to have come all at once usually has a long series of steps behind it. Humanity has faced down tyrants before, valued institutions have been torn down, and built up. Healing may take generations, but healing does come. Change may take a while, but with consistent effort, it can come. We play the long game.

5. Engage in Venn Activism

One thing I have been thinking a lot about over these past few months since the election is something I’ve come to call Venn Activism. I’ve shared this before at times. We know we can not confront the challenges that face us alone, we need to form coalitions with those with whom we are in solidarity. We can not also just leave issues to those who are directly affected, we need to look out for each other and serve as allies and support to those who are being directly impacted.

A Venn diagram is that visual representation of the similarities and differences among groups, a visual representation of data as overlapping circles with the similarities in the overlap and the differences in the other parts of the circle. Each circle represents a group or subset or whatnot.

When it comes to community work, coalition building, and social justice work, I use it to mean that we are going to need to form relationships with groups with which we are not aligned 100%. And this is not only OK, but necessary. If each circle is a group or organization, the intersection of the circles of the diagram is the issue that we are working jointly on. The other part of the circle are other issues and ideas that are not in alignment or the basis for the coalition. Our challenge, then, is to focus on the overlap of the Venn diagram, rather than what is in the other part of the circle. For if we require that the groups we work with overlap completely, we will not be able to move forward.

An example is our interfaith work, in which we are in coalition with faith communities that may not share our values, whether it’s on gender and leadership, or reproductive freedom, or the celebration of queer lives. And it puts us in relationship with those who might not have a full understanding of what Judaism is, and how we approach text, spirituality, and practice. And even within the Jewish community, we are at times expected to collaborate with more traditional Jewish communities, knowing that we differ in approach not only regarding gender for example, but to Jewish practice, Jewish identity, Jewish continuity.

And yet, times dictate that we do cooperate at times. The onus when we are forming these Venn coalitions is twofold. One, we need to be clear what issues we will work on together, where the overlap is, and what issues we are not going to work on together. And two, we need to not let the overlap suffer for these other distinctions.

So often in these circles we enter with ideological purity, litmus tests that one group imposes on another, tests that say that unless there is 100% agreement on every issue, then it is impossible to move forward together. But that is not going to be effective in the long run as we will inevitably need to work on issues of common concern with groups that we may fundamentally disagree with on other issues. We need to approach drawing these Venn diagrams with self-awareness and transparency and humility.

I say this knowing that Jews have always faced litmus tests as a condition for acceptance in the greater society. And I think within the Jewish community too we are often subjecting each other to litmus tests–that there needs to be complete alignment on certain issues in order to cooperate or feel belonging.

This, I think, hurts us in the long run, because to live in community, or a congregation like ours that is dictated not by ideology but by geography primarily, is to live with people who are unlike you, yet bound together commitment to Judaism and the Jewish people. What that means for each one of us is different. But to live in Jewish community is to live with humility, recognize the differences, and to continue to actively choose and accept them along with what holds us together.

Can we be, for example, a community that welcomes all forms of Jewish spiritual expression, even when it is difficult to appease everyone at all times?

Can we be a community that welcomes and includes various views of Zionism with the understanding that we are all committed to Jewish continuity and survival?

The onus isn’t solely on the community, it’s on each one of us. If our relationship to community is conditional, then are we really committed? Because in that case we are not allowing for our presence to be a part of the growth and change of others. And we are not allowing for ourselves the possibility for your own growth and change. The participation of each one of us is a gift to each other.

The circles of our Venn Diagrams are always shifting, but they will guide our work moving forward.

6. Don’t Punish Others for their Past Selves.

As we gather over these High Holidays, these days of consequence, we do so with the intent of confronting who we were, who we are, and who we want to be. The work of teshuvah, repentance, is not easy, for it means an honest assessment of what we have done, and making firm commitments of what we wish to do. And this is all the more difficult when we have caused harm, and need to make amends with others.

One aspect of teshuvah that can be difficult, is that even when we have done the work, we can not undo the past, and we may still live with regret for what we have done in the past. And worse perhaps is that others will remember.

Our tradition understand this, and teaches in the Mishnah (Bava Metzia 4:10):

אִם הָיָה בַּעַל תְּשׁוּבָה, לֹא יֹאמַר לוֹ: זְכוֹר מַעֲשֶׂיךָ הָרִאשׁוֹנִים.

“To one who has done teshuvah, do not say, remember your past deeds”. You are not allowed to remind someone who has done the work of teshuvah about the wrongs they did in the past. You are not to punish someone for their past selves.

And yet we do this all the time. Sometimes in our interpersonal relationships we bring up past harms, undercutting the work of teshuvah. But also in our coalition and movement building in these moments. Someone who takes longer to come on board, or change their mind, or whose learning process is slower, we don’t always welcome with open arms, but say, “well its about time,” or “we have been here from the beginning, where were you?”

Like the 40 years in the desert, some things take more time to build. Some people take more time to change. Not welcoming others undercuts this work. These are all hands on deck moments. The coalitions may vary, the Venn diagrams may change, but we must—as I read in an article shortly after the election–treat our “opponents” not as “enemies” but as “future allies.” We must approach everyone with openheartedness, with curiosity, with affection. And we too must be open to change, to new insight, to new understandings.

Everyone has the ability to grow and change and learn. That is the meaning of these High Holidays.

7. Don’t Forget Joy

I must admit, I’ve become a bit of a cynic around joy. I wonder how to feel it during these times when there is so much fear and suffering. We open up the newspaper, and the same newspaper reports on the latest horror in the same breath as the surging Mariners, or the latest fashion trend, and I struggle with the seemingly superficial in light of the horrors that are surrounding us.

But that initial reaction is a reminder perhaps that joy doesn’t come naturally, perhaps, that we need to exercise our capacity for joy as much as we do anything else. So then I pause and remember that in the course of a month I would have stood under the huppah with three different couples, that I look around and see our community here at TBH is undergoing an incredible baby boom and the happiness and joy that comes from being around littles–especially now as I mentioned both of my children are formally adults. It’s surprising and invigorating.

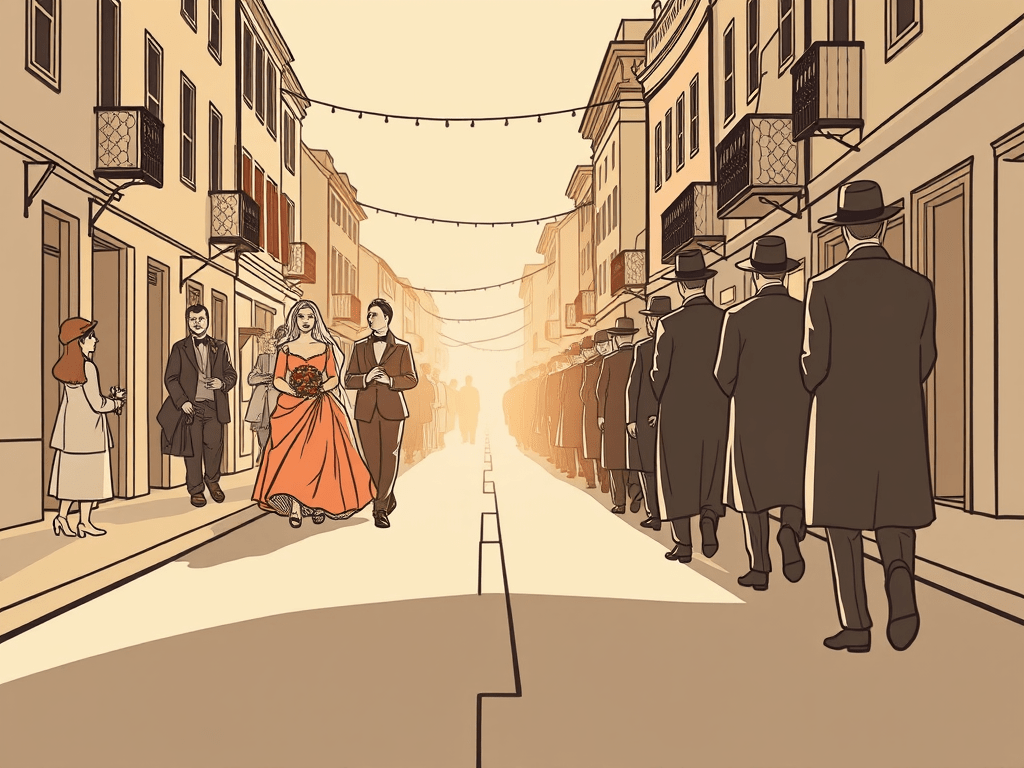

It is imperative that we find these moments of joy at times of challenge. There is a telling passage from the Talmud of our ancient rabbis who are having a series of discussions around various wedding practices and traditions, the rabbis teach (Ketubot 17a):

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: מַעֲבִירִין אֶת הַמֵּת מִלִּפְנֵי כַלָּה

In other words, if there is a wedding procession coming down the street and a funeral procession coming down the street opposite at the same time, the funeral procession defers to the wedding procession. The idea being, that while we recognize the reality and pain in our lives, in our world, we must not let that erase the joy and happiness that we also find. There is death and life at the same moment. We mourn the loss, but yet we make way for joy. It’s not a conceit, it is necessary.

And it is not just a means of survival. It’s a means of resistance. If we are able to continue to find moments of joy during times of hardship, then we know that we are not overcome and defeated, and we have the ability to envision a better and renewed world—the world as it could as it should be.

Seven ways to meet this moment. These have not been easy times, nor do I expect them to get any easier in the near future. And there will be more to share in these holy days ahead. And if there is anything that weaves throughout these seven ways to meet the moment that I offer you this evening it is this: you are not alone. Your are not alone. We are in this together. We will meet this moment, and transcend it, together.

Leave a reply to Rabbi360 Cancel reply