Well these are interesting times we are living in.

It is always noteworthy how the High Holidays come in the fall, when so many of our other renewals and new starts take hold. In nature we transition from summer to fall, and are harvesting the last of our summer bounty. The salmon are running, making their way upstream to spawn and start a new turn of their lifecycle. Students, young and old, return to school after summer break. Baseball season winds down as football season begins.

And I did not notice until last year how closely the High Holidays fall to our American election cycle.

Our election day falls about 6 weeks after these holidays, and so depending on the year, our thoughts come fall are also on our governance, on our elected leadership, and the different visions they set out for our country. As we gather to make these new commitments to ourselves, our traditions, and our communities here within these walls at this season, we also, as a country, prepare to make new commitments as a nation as we prepare to elect our new leaders.

And because of this, the reality that we are in at the High Holidays can change so drastically just a short time after.

And so it goes without saying, that as we gather on this Rosh Hashanah we are indeed living in a different world. Last year at this time the election was close at hand, and we perhaps had different ideas about where we would be this year. For some, a welcome change, for others not. But in any event it warrants a reexamination of where we see ourselves in our world.

Every year at this time, Erev Rosh Hashanah, it is an opportunity for us to reflect and review. As I call upon you to do this work, so too do I do it myself. And I have the privilege and opportunity to share with you the results of some of that reflection. I have stood before you and shared different lessons I have learned about life, about teshuvah, from experiences from the past year.

Maybe you have been keeping score, but these include what I have learned from having a child, from having surgery, from having a backhoe hit my house, from me hitting a car in a parking lot. From Legos, from the Seahawks, from a garden. And last year, from losing a binder full of 18 months of work. (Which I might add, no one has returned to me.)

And so tonight, looking over the year I have had since these past High Holidays, I present to you the six things I have learned since last year’s election.

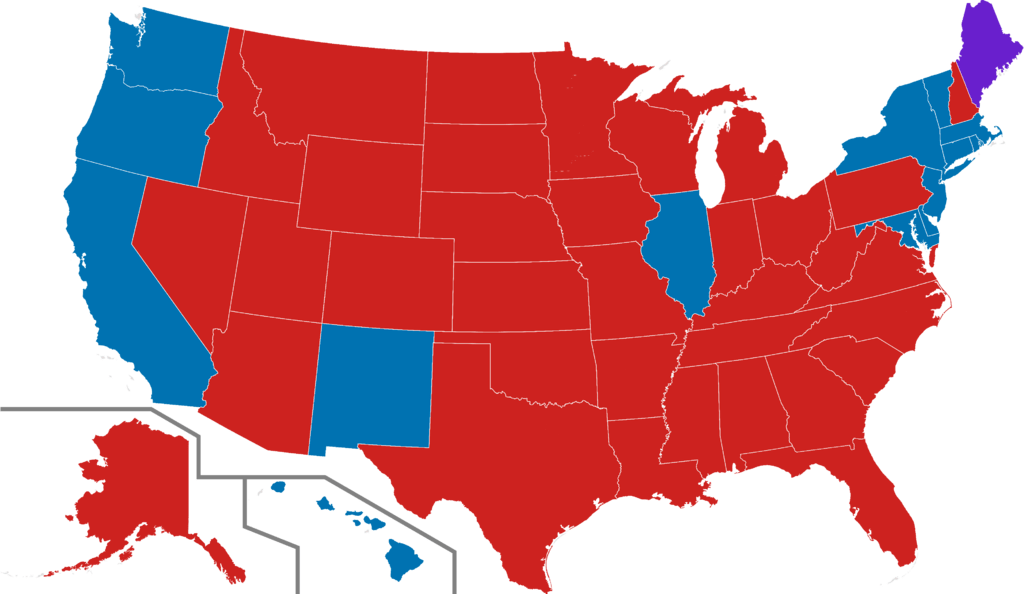

We Can Not Predict the Future. Yes, the polls were wrong. So many of the polls were wrong. I remember thinking in the days before the election confident that my candidate would win, based on what the polls were saying and how the path to victory seemed clear, or that the paths that would lead to defeat seemed that much more difficult. News outlets posited scenarios, and most of them went one way. But as we watched the returns come in, seeing the result that I along with many others did not anticipate, a new understanding set in.

And that understanding is not necessarily that the polls were wrong. That is a reaction, to go back over the data and methodology, to see what was overlooked. But rather what this should come to teach us is that we humans are unpredictable. Life is unpredictable. Yet we crave certainty, we crave control. We want to break down human behavior to data points. But we can not be broken down into data points. We are too complex, too irrational for that.

We remember this not only in times when polls are proven wrong, but we remember this every day, in our interactions and relationships. It is what we are meant to particularly remember at the High Holidays. Its why we seek forgiveness for our imperfect, unpredictable, irrational selves. And why we should grant forgiveness as well.

We Do Cheshbon Hanefesh on Many Levels. The work that we do on the High Holidays is cheshbon hanefesh, roughly “soul accounting.” We take an inventory of what is inside, what is going on for us. In the classic sense, we look at our character traits, or middot. Where have we done well in the past year, and where can we do better.

And while we often think about this work in the context of repentance, of turning away from bad deeds, it is more than that. To do cheshbon hanefesh is to get a better sense of self, to understand who we are and how we operate in the world. There may be some traits we want to highlight and augment, there may be others we wish to downplay and control, but all of them make up who we are, and the process brings us to a better understanding of who we are.

Since this election we have been asked to do this on multiple levels. Not only to know our spiritual make up, but our societal make up as well. We are challenged to examine who we are in the world, and how certain traits, certain identities operate in the larger whole. We have been asked to examine privilege and power, when we hold it and when we don’t. And the act of doing so—of doing this type of cheshbon hanefesh—allows us to more clearly work to create a society that is just, equitable, and free from oppression.

And this examination again reminds us of the complexities we hold as people, that we are beyond labels, just as we are beyond poll numbers. We have intersecting identities. We hold privilege in some aspects of our identities and not in others. And we honor this complexity within ourselves and others for it is this complexity that makes us human, and allows us to see each other as whole, as fallible, and therefore as worthy of forgiveness.

Don’t Just Resist, Persist. Resistance is the name of the game these days, as those who seek to advance an agenda not represented by the current administration claim the mantle of resistance, of opposition, of fighting back. It is, regardless of the specific issues or the specific make up of the government, the common trope throughout history—of standing up to an unjust power structure and demanding change.

Resistance is part of our sacred traditions as Jews. Abraham stood up to God, challenging God on a plan to destroy the cities of Sodom and Gemorroah with the most chutzpahdik Torah verse there is: “Shall not the God of justice act justly?” Moses stood up to Pharaoh, demanding freedom for his people after decades of oppression under a tyrannical regime. Our sacred narratives are one of resistance.

But with resistance comes persistence, for we know that movements are not built overnight, one single act of challenge is more often than not ineffective. We need to persist. Abraham would not take no for an answer, and argued with God, bargaining to save the cities if just 10 righteous people could be found in them. Moses returned time and time again to Pharaoh, making the same demand over and over again, each accompanied by a different plague, which, we could posit, were 10 acts of political demonstration.

And so too with personal change. We may resist ways we have been in the past, resist bad habits and behaviors that ultimately we wish to change. But change comes not just with resistance, with the idea of change, and not just with isolated acts, but with persistence. With the knowledge that we have the power to change, and that change comes when we are able to continue a practice that is sustainable.

“Go big or go home” is an idiom that has entered our language in the past few decades. But what we need is go big or go small. We need those grand gestures, the big visions. But we also need the small actions, the reachable goals. Organize that big demonstration, and call your legislators. Have a grand vision of how you want to be, but make that change a little bit each day.

Be Prepared to be Surprised. For many, the results of the election last November were a surprise. And it seems like there is a new surprise every day since last November. But that is the nature of life, to be surprised. Life is surprising us every day, sometimes for good, and sometimes for bad. And this fact is both the greatest joy and greatest challenge of life.

The Catholic theologian Henri Nouwen wrote, “Let’s not be afraid to receive each day’s surprise, whether it comes to us as a sorrow or a joy. It will open a new place in our hearts, a place where we can welcome new friends and celebrate our shared humanity.”

We must open up our hearts to surprise, for it can change us. And we must open up our hearts to the possibility to be surprised, for surprise may come even when and from whom we least expect it. Our challenge is not to accept how things are as a fait accompli, but rather as the status quo from which we have the ability to change. And even when the surprise is not expected or welcome, we learn to grow and persevere as well.

One of the greatest gifts we give to ourselves is the gift of anavah, of humility, the acceptance that we do not know all the answers, that we have the ability to be wrong and to grow from that being wrong, that we are sometimes at the mercy of forces beyond us, and we have to live with that fact. That is what allows us to tap into the meaning of these days. The overall theme of the High Holidays is that we have the power to change, that our fate is not set in stone, we can remake ourselves and others can remake themselves. Who we are at one point in our lives does not mean we are that way in another. The same is true for others. And one of the greatest gifts we can give to another is to honor their ability to change and, perhaps, surprise us.

Find What is Common Through Difference. It is cliché at this point to say we are divided. We withdraw into our corners, tune into the news sources that validate our opinions, and spend our time with like-minded people. Our political situation, especially since the election, exacerbates this condition through word, and deed, and tweet, with political divisions becoming deeper and deeper leading to real alienation between people.

Some divisions may never be breeched, and I do not think we need to engage with those who would not seek to engage with us, or profess a level of hate so as to dehumanize others. Oppression is real. Abuse of power is real. And there are those who base their worldview on these premises.

But for those others, with whom we may share merely a difference of opinion, it may be worthwhile to continually remind ourselves of our commonalities. To remind ourselves that we all have common desires, and needs, and even shared values. That we share a common past, and a common future. And our commitment to these commonalities, to relationship, to community, should be more powerful than these disagreements.

I raise this as a concern especially around the Jewish community. There is trouble within Jewish communities—made more and more stark since the election perhaps—as more and more there are litmus tests being applied as to who can be in and who can be out. This is deeply disturbing to me, both when lines are being drawn, and especially when lines are drawn artificially. When an opinion is projected on another to bolster one’s own. We Jews can and must be able to weather our own internal political divisions—there is too much at stake for Jewish community and Jewish continuity. I say this broadly, and I say this about Olympia. Jewish community is complex and messy because humans are complex and messy. But for the same reasons, it is able to change and adapt. It is not one thing because we are not one thing. And to separate oneself from community, because others share a different opinion, and to exclude others from community because they share a different opinion, is detrimental and does not allow ourselves to learn and grow from each other. The community is greater than any one of us.

Make Eye Contact, Make Small Talk Following the election, a history professor from Yale named Timothy Snyder wrote a short yet powerful book, called On Tyranny. He draws 20 lessons from the history of the 20th century and applies them to today, lessons from what could be said to be the worst of the past 100 years and how we can learn from them.

The one chapter that stood out for me is number 12, “Make Eye Contact, and Make Small Talk.” He writes,

Tyrannical regimes arose at different times and places in the Europe of the 20th century, but memoirs of their victims all share the same tender moment. Whether the recollection is of fascist Italy in the 1920s, of Nazi Germany of the 1930s, of the Soviet Union during the great Terror of 1937-1938, or of the purges in communist eastern Europe in the 1940s and 50s people who were living in fear of repression remembered how their neighbors treated them. A smile, a handshake, or a word of greeting—banal gestures in a normal situation—took on great significance. When friends, colleagues, and acquaintances looked away or crossed the street to avoid contact, fear grew. You might not be sure, today or tomorrow, who feels threatened in the United States. But if you affirm everyone, you can be sure that certain people will feel better. In the most dangerous of times, those who escape and survive generally know people whom they can trust. Having old friends is the politics of last resort. And making ones is the first step new toward change.

This reflection by Snyder can also be understood as a new and important understanding of that famous verse in Leviticus 19, “you shall love your neighbor as yourself.” This verse we usually read as a sweet sentiment, or as an ethical imperative. And though it is both of those things, the fact of loving your neighbor can also be all that stands between saving a life and losing it. And between saving or losing ourselves. For it must not be just love your neighbor. It’s know your neighbor. Protect your neighbor. Defend your neighbor. Shelter your neighbor. Provide sanctuary for your neighbor. We Jews, in our history, know this all too well.

And when we do this, we are living into the true spirit of Judaism itself—that no one person is more important that another because we were all descended from the same spiritual ancestor and are all made in the divine image. As Snyder writes: Affirm everyone. Affirm everyone.

This election has brought to light division, hatred, pain, supremacy in ways unprecedented in modern times. And it has given us an opportunity to confront what is wrong, identify a vision of what is right, and harness our power to set a course for ourselves and our communities towards an ideal of something new and better and greater than ourselves.

That is what we have committed to since last November. And that is what we commit to every year, at these most sacred days.

Thanks for continuing the conversation!