My sermon from Yom Kippur this year. I forgot to post it here until recently!

I don’t know where you are getting your news from these days, but one of my go-to sources is the Onion.

If you are not familiar with the Onion, it is a satirical newspaper that has been around for a while. It is strikingly funny, and like all good satire, carries with it a bit of pointed truth. For example, after a mass shooting, they run the headline “No Way to Prevent This, Says Only Country Where This Regularly Happens.” This headline is in itself sharp and funny, and the other part of the joke is that they have rerun this same headline for over a decade.

Earlier this year, the Onion ran a story with the headline, “Disgusted God Puts Giant Overturned Glass Atop Humanity.” The story reads how God noticed humans were infesting the earth:

Heavenly sources confirmed the Almighty cursed in surprise when He first spotted the massive swarm of human beings crawling through Creation, but He soon scrambled to overturn a 70-million-foot-tall drinking vessel and contain the planet’s infestation, trapping the enormous mass of 8.1 billion squirming pests inside.

“Gross, gross, gross, they’re getting all over the place!” said the visibly nauseated deity, who after a short search around His Kingdom retrieved a 10,000-mile-wide paper plate He could slide beneath the glass to ensure the scampering throngs didn’t escape. “Ugh, I hate the twitchy way they move. And the tiny hairs all over their bodies. Plus, they’re always kind of moist. Totally creeps me out.”

This is something we can relate too. Not only because we are now entering spider season here in the northwest, but again, how the best satire carries a bit of truth, the idea the humans are an infestation needing to be contained perhaps raises in us a tinge of recognition.

This article from the Onion struck me too because it reminded me of an ancient midrash—rabbinic commentary—from the Talmud. Really.

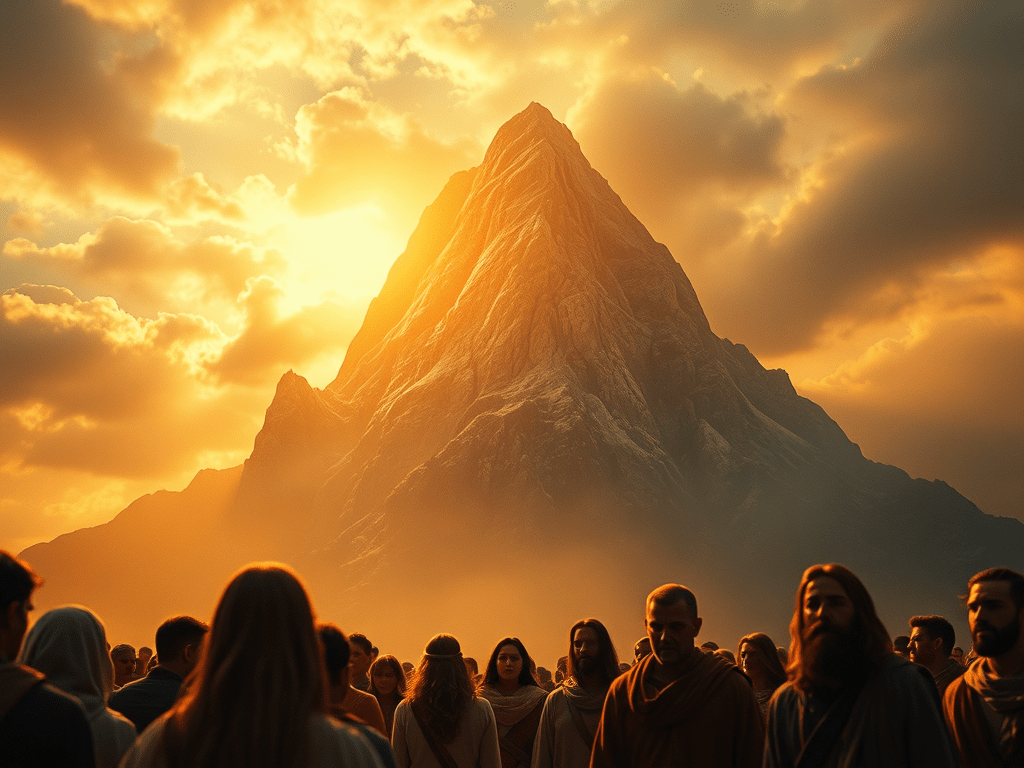

The rabbis are discussing the story of the revelation at Mount Sinai, the story in the Torah how God gave the Torah to the people through Moses thereby establishing the covenant. As the story is told the Israelites left Egypt after their liberation from slavery, and marched through the wilderness to Mount Sinai, where they encamped and made their preparations. We read in the text:

On the third day, as morning dawned, there was thunder, and lightning, and a dense cloud upon the mountain, and a very loud blast of the horn; and all the people who were in the camp trembled. Moses led the people out of the camp toward God, and they took their places at the foot of the mountain. (Exodus 19:16-17).

This is the description from Exodus of this seminal event. We can imagine the experience. Especially since we just blew the shofar last week, the loud blast of the horn, we can imagine the sensory overload this experience was meant to bring, signifying the importance of this moment.

Rabbinic commentary, or midrash, can be based on multiple factors: it could fill in the gaps in a story, adding details that are seemingly missing. It can resolve inconsistencies, or draw parallels between texts. And sometimes, a rabbinic commentary can be based on a very close reading of a word. Such is the case here.

This last clause of the Torah text—”they took their places at the foot of the mountain”—the rabbis note that the word used for “the foot of” is be’tachtit. And that word is related to the word tachat—which means “underneath, or “below”. So the rabbis teach:

Rabbi Avdimi bar Ḥama bar Ḥasa said: the Jewish people actually stood beneath the mountain, and the verse teaches that the Holy Blessed One overturned the mountain above the Jews like a tub, and said to them: If you accept the Torah, excellent, and if not, there will be your graves. (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 88a)

Now this is an interesting and somewhat problematic midrash. For it posits, and the rabbis understand this, that the acceptance of Torah and of the covenant was in a way coerced. And for the rabbis, they wonder, what is the validity of the Sinai event if this is the case. And today, at a time in which we are all continually choosing Judaism, making it our own, finding our own meaning in it, the idea of coercion is anathema to a spiritual life that into which we freely enter.

And I would tend to agree. But this midrash still piques my interest, and I want to offer you a slightly different read. And maybe it’s a little chutzpahdik of me to offer a different reading than the Talmudic rabbis, but its based on another close reading of the text. When I first heard this midrash, I imagined the meaning of “there will be your graves” refers to the dropping of the mountain on top of the Israelites, thus immediately squashing them, like the giant foot from Monty Python or something like that.

That’s how I imagined it. And maybe that’s how you imagined it when I first read this text. We can imagine Mount Rainier over there being held up and dropped.

But again, individual words are important. For the midrash speaks of God holding the mountain over them “like a tub”—which in Hebrew is gigit. A gigit is a vessel, a reservoir, also a technical term for a tank used for brewing beer.

Now I don’t know enough about ancient geology to know whether or not it was assumed that mountains were hollow. But in this case, they do, and so God is holding the mountain over the Israelites not like a giant rock, that is solid, but like God in the Onion story, like an overturned glass or vessel. The danger, therefore, in dropping this on the Israelites is not an immediate demise, but a gradual one. Not the immediate eradication of the people all at once, but the slow suffocation off of a trapped population.

In other words, when God is imagined as saying “If you accept the Torah, excellent, and if not, there will be your grave” the meaning is, if you do not accept for yourself a system of values, morals, guidelines, and norms, then you and your entire community will slowly become irrelevant and die out. The mountain is over your heads, you must learn to live by these values and teachings, God is saying, or you will not survive—not because I will kill you, but because you will kill yourselves.

And so what I think this story of the mountain over our heads comes to teach, what the rabbis intuited, what seemingly God knows but we need to learn, and what I feel has been proven over and over again over these past few years, is that we, as humans, by nature, are not empathetic beings. We do not know empathy naturally. We need to be taught empathy. We need to be taught how to see beyond ourselves. It does not come naturally to us.

As the late poet Andrea Gibson put it so eloquently, “coming into our own humanity often takes enormous effort, commitment, and bravery. I believe part of the violence of our culture stirs from the myth that kindness is natural. I don’t think kindness is natural…So kindness is work. Kindness is our knees in the garden weeding our bites, our apathies, our cold shoulders, our silences, our cruelties, whatever taught us the word ‘ugly.’” (Take Me With You, p. 125)

Hearing this, there is a reason, perhaps, that the Torah begins in a garden. We need to cultivate kindness, empathy. We need to plant it, tend to it, grow it, weed around it, because it will not grow on its own. We have seen demonstrated these past few years a distinct lack of empathy, and with that our ongoing state of grief.

And we are grieving. We are grieving because have seen laid bare the human tendency towards power, towards individualism, towards narcissism, towards ego that is dividing us, that is harming us, that is killing us.

We are grieving because we our US government and its leadership is literally trying to kill us, by cutting access to health care, defunding medical research, opposing gender affirming care, marginalizing the disabled. We are hurt because our government is persecuting our friends and neighbors based on citizenship status and skin color. We are hurt because our government is treating many of us as disposable in order to maintain an oligarchy, an elite.

And as Jews, we must speak about one of the greatest sources of grief, the situation in Israel and Gaza. Since October 7 our collective vulnerability, fear and pain as Jews has taken a dominant role in our minds. At the same time is no denying the fact that the subsequent assault on Gaza, has been a colossal moral failure of the state of Israel and the Jewish people. I firmly believe that the leadership of Benjamin Netanyahu and his ultranationalist allies have failed us, have failed the Jewish people as leaders, and we must be horrified at the forced displacement of Palestinians, the intentional starving of the population, the bombing of children, the collective punishment on an entire nation–all in our name and the name of Jewish safety.

And we are in grief because often in response to our pain we take it out on each other, create division, cancel each other, sever relationships.

We are grieving because we as humans continue to prove time and time again that unless we learn empathy, we will not live empathy.

And this is the mountain hanging over our heads. This is the message: you must create a new reality and or you will dig your own graves. We as humans can not be left to our own devices, to our innate natures, we will only cause and perpetuate harm. Recently I heard Jane Goodall, who passed away just this morning, speak on a podcast, vibrant and erudite to the end, describing how we humans are highly intellectual, but we are not intelligent, because we are intent on causing harm. We are intent on destroying our home.

We humans are so adept at causing harm, I would suggest it is only if we have a sense of the spiritual, a grounding in values and traditions, that we can perhaps transcend our nature to achieve something greater. Indeed, one of the powerful roles spirituality plays in our lives is how to encounter and navigate grief, this grief that we are creating.

There is another similar teaching in the Talmud that I turn to often, that I have shared with you, that discusses a Talmudic debate between two houses of study, Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai, who are notorious sparring partners:

For two and a half years, Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel argued. Beit Shammai argues it would have been preferable if humans had not been created than had been created. And Beit Hillel argues: It is preferable that humans had been created than had not been created. Ultimately, they were counted and concluded: It would have been preferable had humans not been created than to have been created. (Babylonian Talmud, Eruvin 13b)

That’s the answer. It’s humbling. The rabbis count and decide that it would have been better if humans had not been created. The question in this text is what did they count? One understanding is they counted votes of the rabbis, with the majority voting for not created. But another is they counted commandments, and the fact that there are more negative commandments than positive commandments—more “thou shall nots” rather than “thou shalts,” indicates that humans should not have been created. The fact that we need to be told more what not to do than what to do means that we are fundamentally flawed beings, because we need more explicit restrictions than permissions.

And this is the same idea of the need to cultivate kindness, or develop empathy. Our nature is not to transcend ourselves, but with guidance we can. Our Torah which we were offered and accepted is a guide to values that allow us to live into our best selves. Our values serve as a means of teshuvah—or repentance—for the innate harm that we are capable as human beings. They are a form of “nurture” to balance out our “nature.”

The value of pikuach nefesh—saving a life—a value that teaches we do anything we can to save lives above and beyond other practices or mitzvot—compels us to push back against policies that will cause harm to the life and livelihood of individuals and communities.

The value of tzedek and tzedakah—righteous giving—reminds us of our obligation to meet the basic needs of those in our communities and not close our hand to those who require assistance, to ensure a fair distribution of resources.

The value of ve’ahavatah l’reicha kamocha—you shall love your neighbor as yourself—leads us to the idea that we can have a commitment to Jewish safety that doesn’t require the dehumanization, subjugation and occupation of another people, that what we want for ourselves is what we should want for others, and indeed, it is this that will bring about true safety and security.

The value of kol Yisrael arevim zeh be zeh—that everyone is responsible for one another–compels us to commit ourselves to our communities, and see ourselves as accountable for one another, embracing across difference not cancelling because of it.

The value of betzelem Elohim is that we are all created in the image of God and must be treated as so, that we are all deserving of love, respect, forgiveness, and compassion—even ourselves, and we should embrace self-love, self-respect, self-forgiveness, and self-compassion.

These values are of course, not exhaustive. I’m sure you can think of others, like, for example, Shabbat that instills mindfulness of our use of time, our use of devices, our need for rest. Or bal tashchit—do not waste—which is a charge to be humble about our relationship with our environment and its resources.

We need to learn and exercise these values. We need a sense of spirituality. For it is through connection to sacred texts and teachings, rituals and practices, that, if we allow them into our lives, can prevent us from becoming our worst selves. The mountain is over our heads.

We are at a difficult moment in our history: as Americans, as Jews, as humans.

As Americans, we are turning our back on our social contract, undermining institutions, giving voice to old hatreds and instilling new ones, abrogating our responsibility to care for the common good.

As Jews, we feel a renewed sense of isolation and challenge while at the same time we are examining what it means to be Jewish, what is the nature of Jewish community, what is the relationship between Jews here and in Israel and across the world, and how do we chart the Jewish future.

And as humans, we continue to demonstrate our ability to dominate, bully, demean, disrespect, and isolate.

But there is promise. There is promise.

For in the end, the Talmudic rabbis describing God holding the mountain say that even though they were threatened with the mountain, the Israelites ultimately understood the value of the Torah and accepted it upon themselves. The Talmudic rabbis debating the merit of the creation of humans recognized that even though we will naturally behave badly, we have the power to do teshuvah, to examine our deeds, and to make better choices.

So here we are, and the mountain is over our heads.

We have a choice.

Will we learn and practice empathy or will we succumb to our base nature?

Do we choose violence, hatred, insult, dehumanization, division?

Or do we choose love, compassion, patience, and mindfulness.

Do we choose the slow descent to our graves?

Or do we choose a renewed, recommitted, re-visioned life?

The mountain is over our heads.

We have a choice to make. We have a choice.

So let’s not let this be our end.

Let it be for us a new beginning.

The mountain is over our heads.

Thanks for continuing the conversation!